Although interactions with dogs may have a positive effect on human mental and physical health, this effect depends on the success of the relationship. Similar to human relationships, the positive aspects of the relationship must outweigh the negative aspects. If the bond is unsuccessful, it may lead to the dog being relinquished to a shelter.

Almost half of the households in the US, and a quarter of the households in the UK have at least one dog. To ensure that dog owners and their dogs can enjoy the mutual health benefits, it is necessary to examine what factors influence the development of a successful bond. In this study, we examined the effect of owner personality, dog-owner interactions, behaviour problems, on the owner’s bond to the dog.

Most research has focused on trying to predict the factors affecting either the human’s or the dog’s attachment, but rarely taken into account what combinations result in mutual attachment. Due to the time restraints of this project, we had to exclude measuring the dog’s personality and the dog’s attachment to the owner, but intend to do so in the future.

Personality is an important variable for relationship satisfaction in human couples. Personality in humans is usually measured through five personality traits: Conscientiousness (self-efficacy, orderliness, achievement-striving), Neuroticism (anxiety, anger, depression), Extraversion (assertiveness, cheerfulness, activity level), Agreeableness (trust, cooperation, sympathy), and Openness/Imagination (aesthetics, fantasy, ideas). Commonly, low Neuroticism, high Extraversion, and high Agreeableness are associated with high relationship satisfaction.

In the current study, we found that Neuroticism was associated with perceiving the dog as a burden and having lower relationship satisfaction, but at the same time, being more likely to see the dog as a source of emotional support (see the post on the new scale for sub-categories). Similar to studies on human relationships, we found that that owner’s with high Agreeableness were more attached to their dogs. However, unlike these findings, there was no significant association with Extraversion. Instead, the attachment to the dog was associated with the owner’s level of Conscientiousness.

Participating in recreational activities has shown to increase relationship quality for human couples. Similarly, engagement and interaction with the dog is associated with the dog’s attachment to the owner, reduces behaviour problems, and increases welfare.

In the current study, we found that the more the owner interacted with the dog, the more attached they were. However, when examining the different kinds of interactions, walking and training your dog was not significantly related to the bond, but playing, petting, taking your dog to new places, and grooming was. This might suggest that owners who are already attached to their dogs are more likely to interact with them, rather than the other way around.

Unexpectedly, the total number of interactions was not significantly related to the dog’s behaviour problems. When looking at the different kinds of interactions, owners of dogs with behaviour problems played less with their dogs and trained them more. It is also possible that this sample was biased. Owners who respond to research surveys about their dogs may be interested in dog behaviour or training, and might be less likely to over- or under-stimulate their dogs, making interactions a less likely factor for behaviour problems.

As seen in previous research, we also found that the owner’s attachment to the dog decreased with the number of behaviour problems. Specifically, owners of dogs with behaviour problems had lower relationship satisfaction, and perceived the dog as more of a burden.

Owner characteristics also had an effect on interaction styles. Owners with higher Agreeableness walked their dog more, those with higher Imagination played more, and owners with higher Use of Emotions (an EI subscale) took their dogs to new places and played more often.

In order to help dog owners and their dogs enjoy the mutual positive effect of physical and mental health, it is necessary to find what factors predict a strong mutual bond. Constructing a personality matchmaking model, and recommendations for frequency and type of interactions, for a successful human-dog relationship, would benefit adoption processes in shelters, and if applied by dog owners, it may prevent animals from being relinquished due to an unsuccessful bond.

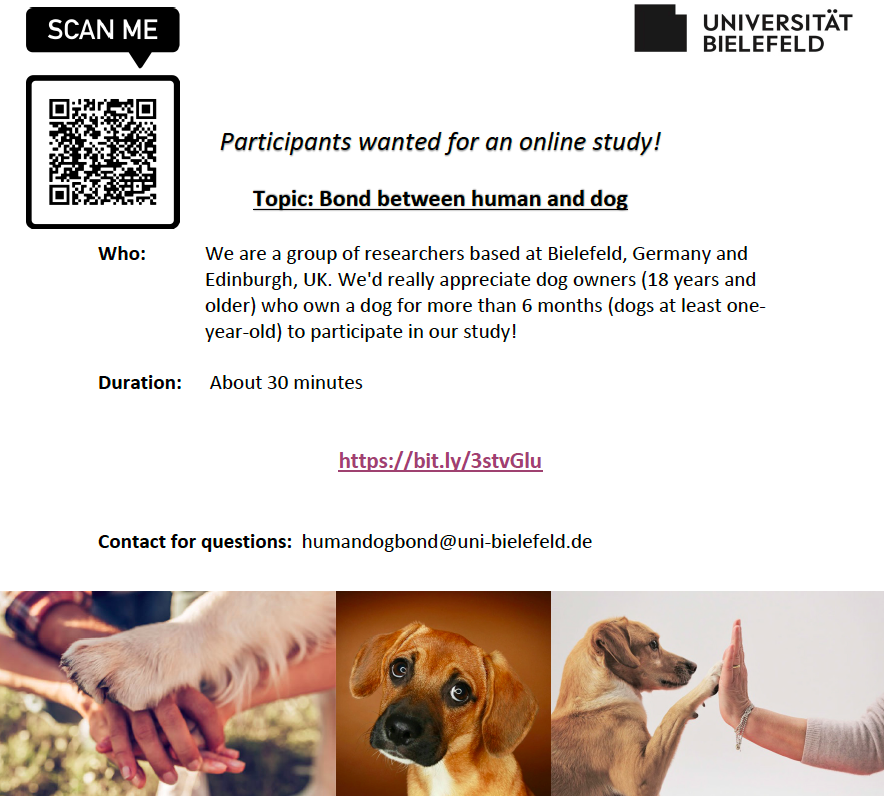

This autumn we will continue our research on the human-dog bond and will be running experiments in Edinburgh on mutual attachment between owners and their dogs. If you are interested in participating, please contact Linnea Lyckberg (l.lyckberg@gmail.com).

Key References:

Cavanaugh, L. A., Leonard, H. A., & Scammon, D. L. (2008). A tail of two personalities: How canine companions shape relationships and well-being. Journal of Business Research, 61, 469-479.

Clark, G. I., & Boyer, W. N. (1993). The effects of dog obedience training and behavioural counselling upon the human-canine relationship. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 37, 147-159.

Curb, L. A., Abramson, C. I., Grice, J. W., & Kennison, S. M. (2013). The relationship between personality match and pet satisfaction among dog owners. Anthrozoös, 26(3), 395–404.

Marston, L. C., & Bennett, P. C. (2003). Reforging the bond – towards successful canine adoption, Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 83, 227–245.

Meyer, I., & Forkman, B. (2014). Dog and owner characteristics affecting the dog- owner Relationship, Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 9(4), 143–150.

Rehn, T., Lindholm, U., Keeling, L., & Forkman, B. (2014). I like my dog, does my dog like me?. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 150, 65–73.

Strong, G., & Aron, A. (2006). The effect of shared participation in novel and challenging activities on experienced relationship quality. In: Vohs, K. D., Finkel, E. J. (Eds.) Self and relationships: connecting intrapersonal and interpersonal processes. New York: Guilford Press, 342–59.

White, J. K., Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (2004). Big five personality variables and relationship constructs. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1519– 30.